In late 1944 as a high school senior I rushed off to a U.S. Navy recruiting station ready to take on world fascism. Cooler heads insisted I wait until my graduation in June. After boot camp I served in “The Pacific Theater”–Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Hawaii, Saipan, Japan, and the China Sea.

In late 1944 as a high school senior I rushed off to a U.S. Navy recruiting station ready to take on world fascism. Cooler heads insisted I wait until my graduation in June. After boot camp I served in “The Pacific Theater”–Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Hawaii, Saipan, Japan, and the China Sea.

Anyone who has gone through school in the United States knows that history textbooks devote a lot of attention to the so-called “Good War”: World War II. A typical textbook, Holt McDougal’s The Americans, includes 61 pages covering the buildup to World War II and the war itself. Today’s texts acknowledge “blemishes” like the internment of Japanese Americans, but the texts either ignore or gloss over the fact that for almost a decade, during the earliest fascist invasions of Asia, Africa, and Europe, the Western democracies encouraged rather than fought Hitler and Mussolini, and sometimes gave them material aid.

From Hitler’s rise to power, the governments of England and France, with the United States following their lead, never tried to prevent, slow, or even warn of the fascist danger. They started by greeting Japan’s attack on Manchuria with disapproving noises, and continued to trade with Japan. It was a prelude to Japan’s 1937 invasion of China.

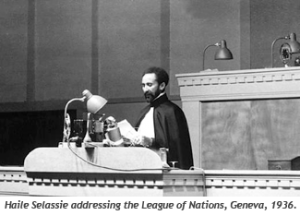

Mussolini, seeking an “Italian Empire” in Africa, threw his army and air force against Ethiopia in October 1935. Fascist planes bombed and dropped poison gas on villages. Emperor Haile Selassie turned to the League of Nations and speaking in his native Amharic described fascist air and chemical attacks on a people “without arms, without resources.” “Collective security,” he insisted, “is the very existence of the League of Nations,” and warned “international morality” is “at stake.” When Selassie said, “God and history will remember your judgment,” governments shrugged.

Mussolini, seeking an “Italian Empire” in Africa, threw his army and air force against Ethiopia in October 1935. Fascist planes bombed and dropped poison gas on villages. Emperor Haile Selassie turned to the League of Nations and speaking in his native Amharic described fascist air and chemical attacks on a people “without arms, without resources.” “Collective security,” he insisted, “is the very existence of the League of Nations,” and warned “international morality” is “at stake.” When Selassie said, “God and history will remember your judgment,” governments shrugged.

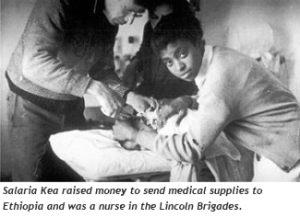

However, in the midst of a worldwide “Great Depression,” citizens in the distant United States were aroused to help Ethiopia. Black men trained for military action–an estimated 8,000 in Chicago, 5,000 in Detroit, 2,000 in Kansas City. In New York City, where a thousand men drilled, nurse Salaria Kea of Harlem Hospital collected funds that sent a 75-bed hospital and two tons of medical supplies to Ethiopia. W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson addressed a “Harlem League Against War and Fascism” rally and A. Philip Randolph linked Mussolini’s invasion to “the terrible repression of black people in the United States.” A people’s march for Ethiopia in Harlem drew 25,000 African Americans and anti-fascist Italian Americans.

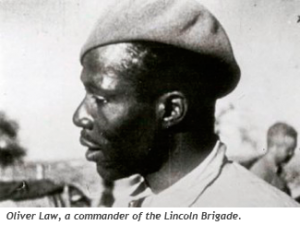

In Chicago on Aug. 31, 1935, as the fascist noose on Ethiopia tightened, Oliver Law, a black Communist from Texas, organized a protest rally in defiance of a ban by Mayor Edward J. Kelly. Ten thousand people gathered and so did 2,000 police. Law began to speak from a rooftop, and was arrested. Then one speaker after another appeared on different rooftops, to shout their anti-fascist messages, and all six were arrested.

In Chicago on Aug. 31, 1935, as the fascist noose on Ethiopia tightened, Oliver Law, a black Communist from Texas, organized a protest rally in defiance of a ban by Mayor Edward J. Kelly. Ten thousand people gathered and so did 2,000 police. Law began to speak from a rooftop, and was arrested. Then one speaker after another appeared on different rooftops, to shout their anti-fascist messages, and all six were arrested.

By May 1936 before many volunteers or help could reach Ethiopia, Mussolini triumphed and Haile Selassie fled into exile. The Americans devotes a puny two paragraphs of its 61 pages of war coverage to this pre-Pearl Harbor conflict. And the drama of democracy versus fascism in Spain merits another whispered two paragraphs in The Americans.

In July 1936 pro-fascist Francisco Franco and other Spanish generals in Morocco launched a military coup against Spain’s new Republican “Popular Front” government. By early August, Hitler and Mussolini provided vital assistance. In the world’s first airlift, Nazi Germany dispatched 40 Luftwaffe Junker and transport planes to ferry Franco’s army from Morocco to Seville, Spain. Italy’s fleet in the Mediterranean sank ships carrying aid or volunteers to Republican Spain, and 50,000 to 100,000 Italian fascist troops began to arrive in Spain. Hitler and Mussolini had internationalized a civil war–and revealed fascism’s global intentions.

But one of the first lessons learned from Spain was fascist aggressors had nothing to fear from the Western democracies. The Luftwaffe destroyed cities such as Gernika in the Basque region of Spain, and Nazi gestapo agents interrogated Republican prisoners. But English and French officials, and their wealthy corporations with financial ties to Nazi Germany, greeted the fascist march with a shrug, quiet appreciation, or offers of cooperation. In England, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin prodded Germany and Italy to march east toward the Soviet Union. The British ambassador to Spain told the U.S. ambassador, “I hope they send in enough Germans to finish the war.”

The Nazi Luftwaffe overhead, Franco’s legions rolled toward Madrid and Franco expected a fast victory. But at the gates of Madrid everything changed. Under the slogan “They shall not pass,” members of unions and political and citizen groups formed military units and headed toward the front carrying lunch and a rifle. Madrid’s women, wearing pants and carrying rifles, took part in early skirmishes. Other women ran the first quartermaster corps.

A scattering of foreign volunteers began to arrive: Jewish and other refugees fleeing Nazi Germany or Mussolini’s Italy, some British machine gunners, and athletes fresh from an anti-Nazi Olympics in Barcelona.

By November the volunteer rush became a torrent: An estimated 40,000 men and women from 53 nations left home to defend the Republic. For the only time in history, a volunteer force of men and women from all over the world came together to fight for an ideal: democracy. The volunteers brought a message that ordinary people could resist fascist militarism.

By November the volunteer rush became a torrent: An estimated 40,000 men and women from 53 nations left home to defend the Republic. For the only time in history, a volunteer force of men and women from all over the world came together to fight for an ideal: democracy. The volunteers brought a message that ordinary people could resist fascist militarism.

Though most volunteers had little military experience, they hoped their commitment, courage, and sacrifice would persuade the democratic governments to unite against the fascist march, and head off a new world war.

But the Western governments ignored Spain’s plea for “collective security.” And some countries outlawed travel to Spain. France closed its border to Spain so volunteers faced arrest and had to scale the Pyrenees at night. England formed a Non-Intervention Committee of 26 nations that blocked aid to the Republican government, but not to Franco’s rebels.

U.S. policy followed England and France. The United States stamped passports “Not Valid for Spain.” The State Department tried to prevent medical supplies and doctors from reaching Spain. The Texas Oil Company sent almost 2 million tons of oil, most of Franco’s oil needs. Four-fifths of rebel trucks came from Ford, General Motors, and Studebaker. U.S. media outlets, isolationist and wealthy groups, and the Catholic Church cheered Franco’s fight against “Godless Communism.”

In the United States some 2,800 young men and women of different races and backgrounds formed the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade.” Seamen and students, farmers and professors, they hoped that their bravery could turn the tide, or at last alert the world to the fascist drive for world domination. Most made their way to Spain illegally as “tourists” visiting France.

In the United States some 2,800 young men and women of different races and backgrounds formed the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade.” Seamen and students, farmers and professors, they hoped that their bravery could turn the tide, or at last alert the world to the fascist drive for world domination. Most made their way to Spain illegally as “tourists” visiting France.

In a time of massive unemployment, lynching, segregation, and discrimination, 90 of the volunteers were African American. “Ethiopia and Spain are our fight,” said James Yates, who fled Mississippi. The United States had only five licensed African American pilots, and two came to join the Republic’s tiny air force (one brought down two German and three Italian planes).

Most of the African American volunteers had marched with white radicals to protest lynching, segregation, and racism, and to demand relief and jobs during the Great Depression. These men and women of color–one was nurse Salaria Kea–formed the first integrated U.S. army. Oliver Law became an early commander of the Lincoln Brigade.

Most of the African American volunteers had marched with white radicals to protest lynching, segregation, and racism, and to demand relief and jobs during the Great Depression. These men and women of color–one was nurse Salaria Kea–formed the first integrated U.S. army. Oliver Law became an early commander of the Lincoln Brigade.

The brave young men and women of the Lincoln and other International Brigades slowed but did not stop fascism. In 1938, fascism’s overwhelming land, sea, and air power defeated the Republic. Many volunteers had died, including half of the Americans, and others suffered serious wounds.

What is remembered as World War II began the next year in 1939, when Germany attacked Poland. It would take a massive, multinational effort to defeat Hitler, Mussolini, and Imperial Japan, and cost tens of millions of lives.

In 1945, world fascism was finally defeated. But for a crucial decade the democracies did not oppose and often emboldened the fascist advance into Manchuria and China, Ethiopia and Spain. But students today don’t learn this. Instead, texts present World War II as an inevitability and the Allies as anti-fascists and saviors of democracy. A fuller history of the failure of the United States to fight fascism at its outset–and even its multifaceted support of fascism–would help students rethink this supposed inevitability. Today’s students deserve more than a few textbook paragraphs describing the fight against fascism before 1939 while the governments of the United States, England, and France encouraged its aggressions.

In 1945, world fascism was finally defeated. But for a crucial decade the democracies did not oppose and often emboldened the fascist advance into Manchuria and China, Ethiopia and Spain. But students today don’t learn this. Instead, texts present World War II as an inevitability and the Allies as anti-fascists and saviors of democracy. A fuller history of the failure of the United States to fight fascism at its outset–and even its multifaceted support of fascism–would help students rethink this supposed inevitability. Today’s students deserve more than a few textbook paragraphs describing the fight against fascism before 1939 while the governments of the United States, England, and France encouraged its aggressions.