By an odd coincidence the first week of Black History Month this February, Time magazine ran an article on the 100th anniversary of the first public showing of the movie classic The Birth of a Nation. This 22-reel, 3-hour and 10 minute silent film was Hollywood’s first blockbuster, first great historical epic, first full-length film (when most ran for minutes not hours), and first to introduce modern cinematic techniques that still keep audiences enthralled.

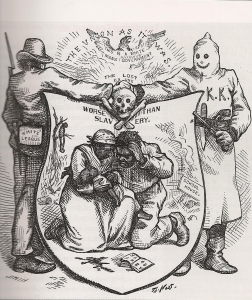

Time noted the movie’s problem. From its casting and content to its dramatic conclusion it was unabashedly racist. (Spoiler: It ends with its armed KKK heroes riding to save “white civilization” from “black barbarians.”)

Time noted the movie’s problem. From its casting and content to its dramatic conclusion it was unabashedly racist. (Spoiler: It ends with its armed KKK heroes riding to save “white civilization” from “black barbarians.”)

This first major box office hit charged a staggering $2 admission, had a special musical score played by an orchestra of 30 at each showing, and reached 50 million people before sound films appeared in 1927. Its millions in profits built Hollywood and made movies a major U.S. industry. Beyond profits, it aimed to educate the public in the values of white supremacy. Thomas Dixon, author of the book and the movie, stated that his goal “was to revolutionize Northern sentiments by a presentation of history that would transform every [white] man in the audience into a good Democrat!”

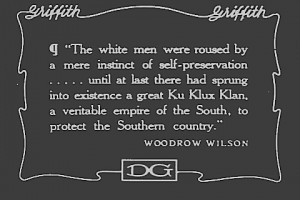

In many cities the showing stirred racist violence against African Americans, and no wonder. White actors put on blackface and played evil African Americans who were grasping for political power over white people—except when they were intent on raping white women. It projected an air of authenticity by using pictures of Lincoln and from the Civil War, and quotes by noted historians such as President Woodrow Wilson.

The Birth of a Nation focused on the period of Reconstruction after the Civil War when formerly enslaved men were allowed to vote and hold office in 11 Southern states. Dixon was a young former Baptist minister in love with gallant Ku Klux Klan stories he heard as a child and decided to write a book, a play, and a movie.

Dixon described Reconstruction as a clash between white good and black evil. He briefly touched history since from 1868 to 1898 African American men under the protection of three constitutional amendments and 25,000 federal troops were elected to office in Southern states. Then his film omits a lot: With white allies, black elected officials helped rewrite the constitutions of Mississippi and South Carolina, elected 22 black congressmen, including two senators from Mississippi, a Supreme Court justice in South Carolina, and a host of state representatives, sheriffs, mayors, and other local officials in 10 states.

This coalition managed to introduce the South’s first public school system, and bring economic, political, and prison reforms to their states, including laws to help the poor of both races and to end racial injustice. Nonetheless, black legislators did not challenge segregation in Southern education, business, or personal life.

After about half a dozen years, as the federal government largely sat silent, these governments were overthrown by KKK violence and systematic election fraud. In 1877 the federal government caved in, made a deal with former slaveholders and withdrew all troops. A democratic experiment was overthrown and white supremacy reigned.

The Birth of a Nation sought to erase any memories of the role of African Americans and the unity they forged with whites to bring democracy to Southern states. The film’s lesson: Race relations must remain in the hands of those who once owned, “understood,” and controlled black people. And white violence is justified to ensure this noble end.

When the movie was shown at the White House, President Wilson called it “history written in lightning.” When it was shown to  members of the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Edward White proudly confided to author Thomas Dixon, “I rode with the Klan, sir.”

members of the Supreme Court, Chief Justice Edward White proudly confided to author Thomas Dixon, “I rode with the Klan, sir.”

The movie also stirred the first large nationwide NAACP-led protests and boycotts. So many black (and white) people marched on theaters that some mayors ordered the removal of lynching and other scenes, or cancelled showings. African American and other historians exposed the movie’s lies, distortions, and omissions. But the most fulsome challenge came in 1935 when W. E. B. Du Bois, the great African American scholar, wrote Black Reconstruction, a thorough history of that era and a documented refutation of the film’s bigoted premise and distortions.

But old racial lies have a high survival rate. In 1950, I was a senior at Syracuse University taking a course on the Civil War and Reconstruction when I read Du Bois’ book as an assignment and wrote a highly favorable report. My professor returned it to me with one word on top: “Nuts.” One of the final exam questions for the course asked students: “Justify the actions of the Ku Klux Klan.” Thomas Dixon, Woodrow Wilson, and Chief Justice White would have done well.

A hundred years after the premiere of The Birth of a Nation, the promise of Reconstruction remains unfulfilled. But this has been a century of antiracist struggle, and it has yielded important results. Sometimes we glimpse these symbolically. In 1915, President Wilson was screening and praising a film that celebrated the Ku Klux Klan and was filled with images of grotesque racist stereotypes. In 2015, President Obama invited the black director Ava DuVernay to the White House to screen Selma, a film that shows how African Americans fought for the right to vote through courageous activism, facing down murderous white violence.

No doubt, voting rights are under attack once again. This time not by robed Klansmen, but by well-dressed, well-educated members of Congress, the Supreme Court, Northern and Southern state legislatures—and their fabulously wealthy backers. So it’s worth remembering that racism comes in different guises. But it’s unthinkable that a film with the racial politics of Selma could have been shown in the White House 100 years ago. And that progress is something to celebrate.