The personal sojourn that led to a book named Black Indians began in the 1930s and my father, Ben Katz, who fell in love with African American blues and jazz music. He first had a large 78-rpm record collection, and then a large collection of African American history books and pictures. I had to be one of the few white kids in the world who went to sleep listening to Bessie Smith, Sidney Bechet and Louis Armstrong, and woke up surrounded by the writings of Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, and E. Franklin Frazier. At a very early age Dad took me to Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black History and Culture which he considered sacred ground. He also organized jazz concert benefits for The United Negro and Allied Veterans of America so I met Sidney Bechet and James P. Johnson in our living room, and Bunk Johnson sitting at our table at the Stuyvesant Casino. Jazzman Mezz Mezzerow introduced me to Louis Armstrong after his Carnegie Hall concert.

I also began to fall in love with jazz, blues and this history.

Dad helped found the Committee for the Negro in the Arts with Charles White, Frank Silvera, Ernie Crichlow and Walter Christmas. Walter and Ernie and Dad became best friends, and I continued I was blessed to meet so many stimulating men and women of color. Before I joined the U.S. Navy in 1945 my senior high school thesis was a 200-page history of jazz—best described as amateurish, emotional and well illustrated.

My 14-years as a New York public school teacher were spent “bootlegging” my new knowledge into my social studies classrooms—to offset the appalling omissions and distortions of the state curriculum and its approved textbooks. By 1967 a small New York publisher issues my Eyewitness, a Black history text I developed in my classes. I had written to Langston Hughes asking for permission to use several of his articles and one evening in late 1966 my phone rang. “What kind of book is it?” he asked. I explain it was a Black history book for young people and schools. His response was immediate and firm, “Don’t leave out the cowboys!” I think he said it twice. “Yes, I have two chapters on them,” I said. “Good, good,” he said, “that’s very important.” I had his permission.

But I had something more. His five words changed my life. I knew the great poet of urban America had grown up in Lawrence, Kansas, was named after his uncles, John Mercer Langston a frontier Ohio lawyer who defended Underground Railroad agents—including his brother, Charles Langston. Another ancestor was Lewis Sheridan Leary, an Oberlin College student who fought and died with John Brown at Harpers Ferry. Langston Hughes also could trace his ancestry back to Pocahontas. My eyes were opening to a new kind of frontier.

I also had become familiar with the pioneering research on Africans and Indians on America’s frontiers by Kenneth Wiggins Porter, a white Harvard-trained university professor. In 1968 when a New York Times Company asked me to serve as general editor of 212 African American reprint classics I had Porter select his best essays for his The Negro on the American Frontier. It appeared in 1971, as did my The Black West. After Professor Porter’s death in 1981 his wife made me curator of his unpublished manuscripts, and I quickly found them a home at Harlem’s Schomburg Center.

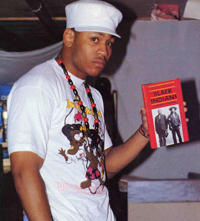

Meanwhile faces of Black Indians—Apaches, Kiowa, Cherokees, Seminoles, and others—peered from the antique photographs I had selected for The Black West. I was looking at America’s first Freedom Fighters, first Underground Railroad conductors, our country’s first “Rainbow Coalition.” My proposal for a book on Black Indians brought only one publisher response—Athenaeum’s Young Adult editor Marcia Marshall.

Meanwhile faces of Black Indians—Apaches, Kiowa, Cherokees, Seminoles, and others—peered from the antique photographs I had selected for The Black West. I was looking at America’s first Freedom Fighters, first Underground Railroad conductors, our country’s first “Rainbow Coalition.” My proposal for a book on Black Indians brought only one publisher response—Athenaeum’s Young Adult editor Marcia Marshall.

Rules of the day for Young Adult books had advantages—it had to be written clearly and informally, use illustrations, explain important concepts, minimize “scholarship” and omit footnotes, and be under 200 pages. These were also disadvantages. Many readers wanted more evidence, scholarship, and deeper coverage—more than 198 pages could provide. Then there were U.S. Boards of Education demands—such as little coverage of Latin America. The final product bent a few rules by using many original sources, historical engravings and photographs as evidence, and provided a two chapters on Latin America.

I am pleased for the opportunity afforded by this expanded edition to offer so much more additional information, documentation, visual evidence, and particularly to introduce many more daring Americans of color.

This essay is from Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage and is copyrighted by the author and publisher.